Post-mortem: writing techniques in 'Leather Babydoll'

Critiquing choices in genre & tone, character, and the climax/punchline for this dark comedy horror short story

We’re back for another post-mortem of a short horror story. This time we’re looking back at ‘Leather Babydoll’. It’s a tiny slip of a story, coming in at around 1k words (a 4-5-ish minute read), and previously published in Elegant Literature magazine.

If you’ve not read it, the following post is chock full of spoilers so it’s best to check it out first:

Leather babydoll

It’s time for a short horror story - this one in epistolary form (i.e. written as if it were a letter). I think this was my first time using this form, but it was enormously fun, and the story was first published in Elegant Literature magazine, issue 19

Okay - ready? Let’s dive in.

Genre - how was ‘dark comedy horror’ conveyed?

I’ve called this a ‘dark comedy horror’, but a reader of a short story magazine won’t typically have any prior notice of the genre, so we have to add clues in the writing.

(Side note: this story probably counts as a slasher-horror too. It’s got unusual deaths, a relentless and skilled killer, home invasion, and other aspects that are typically slasher-y, but slasher afficionados might feel otherwise.)

The first clue is the epistolary form.

This is a fancy way of saying the story is written in the form of letters.

It’s very much a classic trope of horror fiction, featuring notably in one of my favourite horror stories - the incredible ‘Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus’ by Mary Shelley (UK link US link - Amazon affiliate links in this post).

In Frankenstein, Shelley uses the epistolary form to layer distance and ambiguity on the events of the story. There are multiple layers of stories and storytellers, with the possibility that at any level the storyteller is simply ‘lying’ about all the lower layers of the story.

We see something similar in ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Emily Brontë (UK link US link), where the whole story is recounted in letters, based on stories told to the writer. This creates some doubt about the veracity of all the events, but it’s consistent enough that we accept the authorial voice and roll with it. (And yes, I count Wuthering Heights as Gothic horror.)

A major advantage of the epistolary form is how it directly creates tone through the first-person voice of the character, while also engaging the reader in the game of ‘can we trust this narrator?’. For comedy horror, this can be perfect!

The second clue is ‘low stakes taken very seriously’

Leather Babydoll starts by establishing incredibly low stakes: it is a reader submitting to a sewing magazine. We quickly realise the letter is from a fanatical reader who probably takes this much more seriously than is necessary.

This is the root of two approaches to comedy:

Take serious things very lightly (e.g. gallows humour)

Take light things very seriously (this is the nature of diagram humour - applying statistical graphing techniques to absurd topics).

This principle of inversion can also bee seen in ‘make cute things dangerous’ (my old Samurai Lapin animations and many Trouble Down Pit webcomic strips were based on this).

In Leather Babydoll, we quickly understand we’re in the territory of the second option: the writer of the letters is taking this very seriously.

The third clue is the tone

It is a truth universally acknowledged that middle-class-people-trying-too-hard are fundamentally suspicious.

Forced, overly polite, or too-formal language comes across as disingenuous.*

In the wonderfully titled academic paper “Consequences of erudite vernacular utilized irrespective of necessity: problems with using long words needlessly” Daniel M. Oppenheimer showed that needless use of complex language lowers the author’s perceived intelligence. You can still use complex words appropriately, but doing so unnecessarily backfires.

I exploited this to build suspicion of the narrator in Leather Babydoll. When she writes:

Is it acceptable for me to address you as Veronica?

… we know we’re in a situation where the formality of the language is likely beyond the needs of the situation. This builds the comedic tone, but is also begins to make us suspicious: what is the narrator trying to hide with their fancy language?

I also called the narrator “Mrs Dorothy Chatsworth”, which was an appropriately harmless English-sounding name. The addition of ‘Mrs’ made this feel extra middle-class which—as any English person will tell you—immediately suggests a seething mass of insecurity, self-hatred, and hidden bile.**

*Yes, I see the irony of using ‘disingenuous’ in this section of my post :)

**Any English person who denies this should be treated with great caution.

Clue four:

foreshadowing

Very early on, our narrator writes:

I will not bore you with the terribly dark times that I have lived through, suffice to say that your esteemed journal was often the only contact I had with the refined and civilised world beyond my boorish family.

While this doesn’t explicitly say there will be descent into horror, it gives an impression the narrator may have a somewhat skewed perspective on the world.

Clue five: escalation

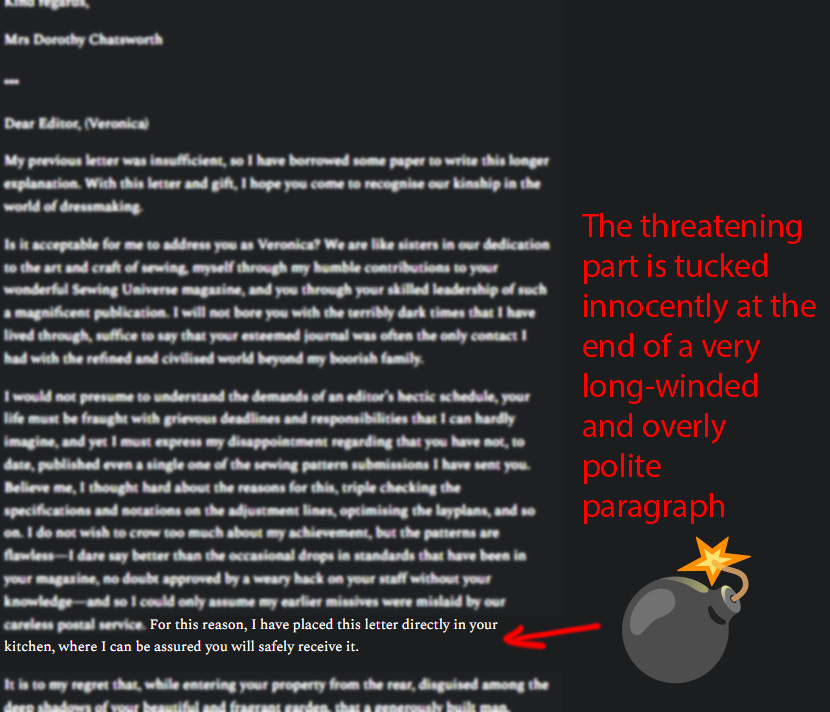

We know we’re stepping into horror when the politest and almost grovelling paragraph ends with the revelation of where this letter has been placed: directly in the editor’s kitchen.

We’re in a terribly, awfully polite home invasion…

The longer the paragraph goes on, the more we suspect something horrible is happening.

Importantly, the narrator remains oblivious to how threatening this action is, but it is clearly a massive escalation of the stakes, and finally tells the reader that worse is bound to come before the letter is over.

Character

The narrator’s obliviousness to the horrific intrusion is key to allowing the rest of the story make sense. She is built in the reader’s mind from a selection of pieces:

Overly polite

Worships the editor (the recipient of the letter)

Has a dark history, where the editor’s magazine was the only ray of light

Obsessed with publication in the magazine

Ignorant of typical social boundaries

Oblivious to the reality that a professional editor of a modern craft magazine might not themselves be a very crafty person.

Part of the joy of writing in first-person is that we can portray reality entirely from the interior perspective of our character: if they see a dragon on a street in South London, a dragon appears to be on the street. Even though we readers know this wouldn’t happen in reality, this doesn’t matter from the narrator’s perspective, because to them it is real.

Likewise, if we have a first-person narrator who values sewing patterns above human life, we can show this is their everyday reality.

Something else to note about this kind of skewed perspective: it’s incredibly fun to write! I’ll have a writing exercise for you along these lines next week.

Climax or punchline?

A few years ago, I listened to a lot of CreepyPasta-style horror stories. Almost all of them seemed to end with a line like ‘And I never went into the woods again’ or ‘I’ve never slept with the lights off since then’. The purpose of this kind of ending is to suggest the horror lingers.*

Another point in common with those stories is the perspective is always from the victim’s viewpoint, never the perpetrator (can wendigos be described as perpetrators?), so this style of ending couldn’t work in Leather Babydoll.

But, this is a comedy, so we can play with this ‘horror lingers’ expectation.

I look forward to seeing my leather babydoll creation in the next edition of Sewing Universe and, rest assured, I will visit again with new patterns in the near future.

Mrs Dorothy Chatsworth, our narrator, remains oblivious to the horror of what she has done. She is confident the editor will be keen to have more sewing patterns in the future: she can ‘rest assured’ this will happen.

Of course, the comedic part is the editor will be threatened by this—not assured at all—but it also maintains the ‘horror lingers’ element. Comedy+horror=punchline.

*I might go into this ‘horror lingers’ approach more in the future.

I’ve just explained a punchline, which is the death of any joke, but I hope you found the dissection and overall post-mortem interesting and inspiring for your own writing.

Next week we’ve got a writing exercise, so I hope you’ll stick around and give it a try.

Have a great week, thanks for supporting this newsletter, and stay spooky!

Mata xxx